A New Exhibit at The Met

A Review of the Last Knight Exhibit at The Met

December 7, 2019

When most people think of a medieval European king, they probably picture something along the lines of Henry VIII of England: a portly man in frilly clothing, who rarely leaves his castle. However, Maximilian I was not that kind of king. Famous for his reputation as a fearless combatant and honorable knight, who hosted tournaments, fought in duels, and engaged in jousting regularly. As Holy Roman Emperor, his singular passion (other than being king) was curating a collection of the finest arms and armor in the realm.

The Metropolitan Museum’s latest exhibit: “The Last Knight: The Art, Armor, and Ambition of Maximilian I” exhibits the fabulous armors, swords, and artworks owned and given to Maximilian over his life.

Although the collection itself is beautiful, and at times mesmerizing, the exhibit really shines in the idea it tries to convey: that Maximilian I was one of the first heads of state in history to effectively utilize media and propaganda to cultivate an image that made him trusted and admired by the people. For Maximilian, that meant the image of a bastion of honor; a knight.

This photo is a set of gauntlets for Maximilian I from 1499

The exhibit presents biographically, starting at his marriage in 1477 to Mary, Duchess of Burgundy and progresses through his life until the time of his death as Holy Roman Emperor in 1519. Maps and text on the walls explain the political situations of the era and make an atmosphere that feels like an early season of Game of Thrones. Throughout, interspersed with cases of armor, barding (horse armor), and assorted helmets are works of art and propaganda depicting the various jousts of peace and war, tournaments, and duels held by Maximilian.

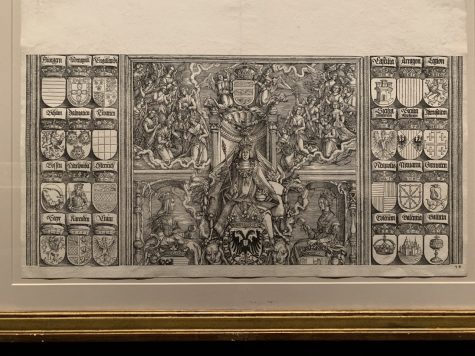

This photo is of a family tree of Maximilian I in 1515, depicting him at the center of royal families all over Europe, from England to Italy and Spain. (Queen Elizabeth the II is a descendant of Maximilian I)

Altogether, “The Last Knight,” tells the story of a man who gained control of a dying kingdom, and consolidated land and power through alliances and public support. Maximilian I utilized his identity as a valorous knight to gain popular favor. As one of the first heads of state to take advantage of the new technology of printmaking, he greatly expanded the role of a ruler as a “public figure”–a paradigm that still exists in modern politics all around the world. “The Last Knight” is interesting not only because of the fascinating history lesson it imparts but also because of how relevant that lesson is.

The Holy Roman Empire was abolished 213 years ago, but the legacy that Maximilian I left behind; the image of a ruler beloved and respected by the people became something that many monarchs and elected leaders saw as a necessary political advantage. On the wall to the right of the exhibit’s entrance, an introduction and dedication read: “Should leaders care what people think of them? Emperor Maximilian I (1459-1519) believed so, and this conviction shaped the way he reigned…Maximilian proved to be a masterful self-promoter. Not only did he care about his subjects’ opinions of him, but he also manipulated them to his advantage.”

If that sounds familiar, it’s because history teaches us again and again about how rulers use propaganda to manipulate public opinion. Maximilian is simply the first to have figured that out. Even in a world with few kings and even fewer empires, leaders still recognize the importance of public opinion. Just replace the word “subject” with “constituents”, and you can make that quote on the wall summarize several American presidencies. “The Last Knight” is a demonstration of the idea that the lessons of history are still relevant today, and that we don’t need to learn them from reading a textbook. Often, the past is preserved in studio lighting, within the halls of a museum.