‘I Want My Credit!’ Young Content Creators and Online Intellectual Property

November 6, 2020

On May 6th, I received my first DMCA takedown notice for a tweet from 2016. The tweet in question was from my 17th birthday where I shared a video from Tumblr of a plush shark getting dressed up to Abba’s “Dancing Queen”. My tweet was promptly taken down and I was not too phased. I had downloaded the video off of a dedicated shark enthusiast Tumblr account using a third-party app. The funny video was not mine to share without crediting the creator @sharkflan on Tumblr but Universal Music Group (the group that reported me to Twitter) was more preoccupied with the fact the video blasted the most popular Swedish group of all time.

The internet is a democratized space where anything you post is a free game. What yours is mine in the Wild Wild West that is social media. The only group that has the power to retrieve their stolen work is branded corporations or artist management teams. Where is the justice for the regular meme maker or content creator? How has the internet shifted into crediting their accessible entertainers?

I’m a Savage

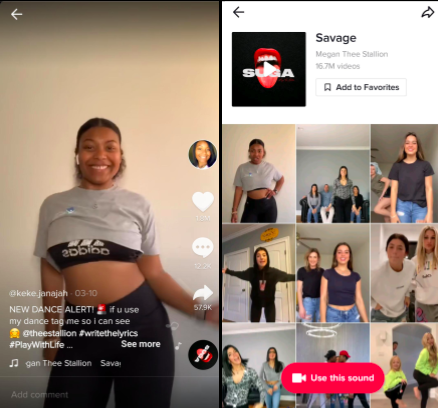

There are millions of anecdotes to show content creators getting their content stolen. The internet has invaded traditional media and will continue disrupting the media landscape. There is no shortage of talented young people online. Amongst the COVID-19 quarantine, many people have been trafficking the popular teen video app, TikTok to cure the boredom at home. It took one good new dance on the ‘For You’ page to go insanely viral and for everyone to spend their time attempting it at home. Keara Wilson started the 15-second dance trend with rapper Megan Thee Stallion’s song “Savage”. It took only a week for Megan thee Stallion to find the 19-year-old Ohio native’s video trending on TikTok and post it on her own social media. Wilson, who before posting the dance, only had 300 followers skyrocketed to over 246,000 followers at the time of our interview. Now, Wilson has garnered 2 million followers on TikTok.

“ It took like an hour or so because I kept switching up the endings three or four times. I’m glad I went with the one I did…I don’t know, I’m just really good at thinking of dances in my head when it comes to choreographing…” explained Wilson about her process of making the TikTok dance.

The “Savage” dance is everywhere but does the internet know where it came from? Like many viral challenges on the app, it’s hard to find the source through the hundreds of people participating in the dance trend. When you search the sound for the song “Savage”, TikTok orders the video with the song by popularity but does disclose with a yellow border that the video is the source of the sound when the sound itself has been uploaded by a creator on the app. Though, music that is also on streaming does not have the yellow border disclosing sound source. Due to this, you need to scroll heavily to find Wilson’s original dance video amongst all of the popular creators on the app. (This has since been resolved. TikTok has seemingly tweaked the algorithm to have Wilson’s video at the top when you search the Savage sound. No other big dance creators on the app at this time have gotten this treatment)

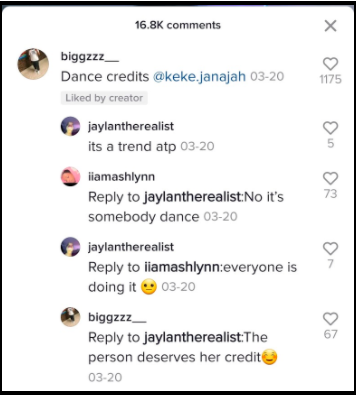

Admittedly, Wilson isn’t having a tough time being credited for her dance. While it’s harder for Wilson to be credited by insanely big stars, she has a support system fighting for her. “It’s my fans. They’ll definitely tell me if somebody doesn’t credit me. They’ll let me know [and] be like ‘dance creds @keke_janajah’ and then they’ll make sure that I get my dance creds”, Wilson explains. While TikTok includes watermarks with the creator’s name, it is very easy for the creator of trends to get lost in the mix. It’s up to the users of the app to police the credit system and it is becoming increasingly important in the dance TikTok realm. Wilson has seen that “Ever since the renegade happened. [People on TikTok are] showing a lot more about being credited”.

The ‘Renegade’ refers to the previously most popular dance on TikTok created by a 14-year-old Atlanta teen named Jalaiah Harmon. Originally, the dance was posted on a different video-sharing app, Funimate but then another TikTok creator, @global.jones simplified the dance and posted their version on TikTok where it became viral. For months until Taylor Lorenz’s New York Times piece revealed it was Harmon who created the dance, no one knew where this dance came from and popular TikTok creators began benefitting.

The aftermath of the ‘Renegade’ left the comments section of dance videos requesting dance credits for all new dances on the app. Wilson welcomes the change seeing how Harmon was for months not recognized for her talents.

“…I feel like that matters cause she’s younger and she could get big off of this. It’s her creativity. So it’s really important.”

Internet: The Wild Wild West

When thinking about copyright on the internet, most remember early internet file sharing websites like Napster which garnered national attention with the music industry suing the site and its predecessors for copyright. Less is studied about the current internet culture of sharing content. Memes have evolved and have become currency in this new digital world. Social media networks have shifted as well.

The internet hit a high in the early 2010s with social media networks like Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter, and Instagram. According to the Pew Research Center, by August 2012, 59% of adults reported using at least one social media website. With that level of engagement to the internet, content got increasingly commodified. Brands made a considerable effort in expanding their social media. Virality was the goal. Simultaneously, on all of the main social media platforms ‘parody’ accounts that consolidated all of the funniest posts, images, and videos on the internet popped up. On Twitter, accounts like @dory and @girlposts stole content from other Twitter users. These accounts garnered millions of followers and proceeded to use those followers to spam the site via Tweetdeck. Tweetdeck is a platform that allows users to create groups of profiles and schedule posts. Administrators of a large group of these parody account Tweetdecks would pay smaller accounts to retweet posts that would spam the tweets on every one of their follower’s timelines. Brands would pay the administrators of the groups to have their accounts added into the mass retweeting. In 2018, Buzzfeed reported that Twitter suspended all Tweetdeck accounts for their incessant spamming and gaming of the social network. Twitter users were mostly glad about not having their tweets stolen by these accounts anymore. While these accounts were suspended, media blogging sites like Buzzfeed and Barstool Sports remain to share content from across social media whether it includes the username of the original creator or not. Consolidated meme accounts on Instagram like @thefatjewish and @fuckjerry still exist with millions of followers.

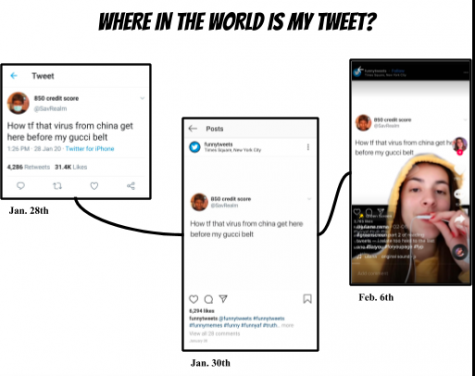

The new norm for a content creator now is to see their content shared all over the internet without their credit or consent. “It usually takes a few days for a tweet to pop up on other apps,” says Lukas Battle (@lukasbattle), a 22-year-old content creator on Twitter and TikTok. “When a tweet of mine goes viral there’s usually a 24-hour span of attention it gets. After it kinda “peaked” I think it makes its way to meme accounts and TikTok”.

Battle started posting on TikTok when he saw other creators using the green screen filter to read allowed screenshots of tweets, specifically his tweets. Battle decided to cut out the middleman and started making TikToks reading out his own viral tweets. The introduction of TikTok in the social media realm has added a new avenue for tweets and memes to be shared. Comedic deja vu occurs when looking at screenshots of jokes you saw on a completely different platform days before. For creators like Battle it’s a phenomenon he’s had to settle with.“I know others have a huge problem with it and I totally get being discredited and not getting paid for your work but I just assume any work I put out on the internet will get reposted and used” says Battle, “When I see my content being used on a big account I usually will politely DM then and ask for credit. Most times they answer and will give credit but a lot of the time they ignore the message”. This large dissemination of reposted work leads the people of the internet to find the origins of their entertainment. Battle’s followers started messaging him whenever they found his posts outside of Twitter with no credits. Battle does not need to be aggressively challenging these meme accounts and TikTok tweet reciters when the internet is already doing that for him.

Credit Mob

The beauty of the internet is that it always remembers and not because there’s an algorithm in place to keep track of codes but people are willing to react and interact within this space.

Speaking of the broader internet, people have always relied on each other for information. They’re always at least one person on the internet willing to do the research. Accounts that want to give credit rely on the internet to do that research. Whether it’s finding a photographer of a certain image or the personal account of someone in a viral video. People use the power of the internet to find talented artists. Yet this all hinges on someone caring enough about the subject to put in that time. Some social media are easier than others when it comes to searching for an original creator.

TikTok is interesting since it automatically watermarks the videos with the creator’s username. The app’s main source is the sounds that when made original can be found through scrolling to see the yellow original banner. While that is how the app is supposed to go, some users have other thoughts. Stealing a sound from a creator and reposting a video with the sound to have the app read your submission as an original sound has become too common on the app. Some creators go back and rename their popular sound with “Don’t Steal My Sound”. Even so, finding a certain sound and crediting an artist is much easier than finding the original creator for a dance. Much of Keara Wilson’s success is her followers’ unrelenting goal to make sure she was being credited for her dance.

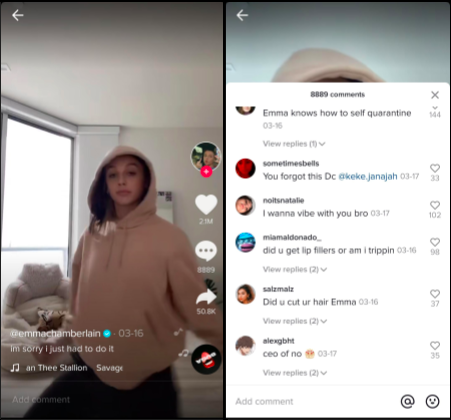

Once the Savage dance blew up countless popular creators on the app and celebrity joined in on the fun but without crediting. Their comments started to become flooded with people telling them they needed to credit Wilson. Emma Chamberlain, a popular Youtuber with over 5 million followers on her TikTok account, posted herself doing the Savage dance at the height of its popularity. “We need to get @keke.janajah to 1 million followers ASAP” commented Chase Davis (@itz_chasee) under Chamberlain’s video.

From the perspective of a fan, not crediting the original creators is one of the biggest offenses of the internet. The internet roots for the underdog in all forms, craving justice for smaller creators who, in bigger media spaces would never get a chance outside of the internet. “When somebody creates art, it’s trademarked, same with dances so I feel like somebody doing somebody else’s dance and getting the credit and publicity for it is wrong.” adds Davis, “Especially the way TikTok’s viewing algorithm works, which leans especially towards white people.”

TikTok tailors your For You page in order of what type of videos you are frequently liking. It has been reported that TikTok does suppress videos of creators from marginalized communities to “prevent bullying” on the platform. Nevertheless, the optics of seeing a white woman join in on a dance trend created by a black woman yet not acknowledge said black woman’s hard work and creativity is rough for this younger generation to see. According to a study done by the Pew Research Center, 66% of Gen Z agree that black people are treated unfairly compared to white people in the US. Naturally, these optics are the first to come to mind when seeing a black creator not receive credit for their content.

“I think the internet is just a digitized version of real-life and shows the real issue at hand, who is getting the real credit and exposure in the industry and in our society? “ says Davis, “Little reasons like social media dances actually make it really clear.”

The Real Cost of Going Viral

The fan comments and credit givers all know that the true cost of what having your content stolen does. Virality is valuable online. It opens so many doors that when creators are erased from the narrative, they are losing social and monetary cachet. It is even more disappointing when these creators are predominantly young and of color.

Lizzo’s 2017 hit single “Truth Hurts” rapidly rose to popularity in 2019 with the infamous line,‘I just took a DNA test turns out I’m 100% that bitch’, becoming a meme. In October 2019, Pitchfork reported that two producers claimed that Lizzo had plagiarized the tune. While their claims were found to be unsubstantiated, it was revealed that the song’s iconic line was from a tweet made by Mina Lioness back in 2017. Lioness is a singer-songwriter that tried to get Lizzo’s acknowledgment of her tweet’s contribution in 2018 but her claims were unfairly dismissed. Lizzo asserted to have “never seen her tweet”. In an interview with Paper Magazine, Lioness expressed “…It’s sad. I’m not asking you for money or anything. I’m just asking for you to believe me…Black women aren’t given the benefit of the doubt… online and offline”. The story ends well with Lizzo giving Lioness a writer’s credit to the song but only two years after it was first released and a year after it’s massive charting popularity. Lioness was only looking for recognition for her work but along the way missed out on a huge monetary opportunity.

Black people have had a big influence on internet culture. Whenever a cool phrase or dance becomes viral, it gets appropriated by big brands and popular influencers. The democracy of the internet is supposed to give any and everyone a chance to express themselves online. For black creators, it means more eyes for people to steal. The most ostentatious example of this kind of theft has to be when Kayla Newman using the name ‘Peaches Monroe’ decided to post a vine of herself in her car exclaiming that her eyebrows were “on fleek”. Newman, who was 16 at the time, quickly lost the recognition for her vine when celebrities’ big brand social media accounts were using the phrase in their advertising. Newman made news in 2017 when she announced that she was in the process of getting on fleek trademarks, securing her intellectual property for her cosmetic business. She was able to acquire the trademark but currently, the legal status of the mark has been dead and abandoned.

The road to trademarking your intellectual property is difficult for anyone but it is increasingly difficult for those without management teams and legal councils at their side. During instances where internet creators try to legally trademark their work, they are met with disdain from others online. The internet is a space where sharing creativity incites more creativity. That is the case for most copyright battles in the media where acts of parody and art are under DMCA violation. The early days of file sharing on the internet shared the opposite sentiment. As the internet grows and becomes a profitable path for many people, the act of self-policing each other became prominent. Content gets stolen or misappropriated so it’s up for the citizens of the internet to get justice.

“This is just this idea of self-policing and what’s called extra-legal opportunities of recourse and extra-legal means, basically outside the realm of the legal system” explains Kembrew McLeod, an author, and Professor of Communication Studies at the University of Iowa, “And that’s where someone who doesn’t have the economic power of a large corporation can still sometimes have the same impact”. McLeod’s book ‘Freedom of Expression®: Resistance and Repression in the Age of Intellectual Property’ studies the development and overuse of copyright and how it is stifling creativity. While the book was published in 2004, the internet has rapidly evolved to assist brands in copyright.

“The organizations like YouTube, Twitter, Instagram, so on where content is shared, it’s up to them to basically write into their code, build into their architecture, a way that credit can be given” incites McLeod, “YouTube uses, content recognition software to recognize if someone’s used the song in the background of their YouTube video without credit. And YouTube has dealt with that by making agreements with record companies”. These systems work for the brands and companies that are profitable and affect website ad sales. There is no programming or artificial intelligence to track when trends are copied or tweets are stolen and put on different platforms.

The notion of self-policing hinges on a personal connection to whatever is being copied to engage in online discourse. McLeod finds it reminiscent of how the comedy community self-policing against joke stealing. The internet has only helped develop that type of regulation by seeing videos posted online. Similar to the comic community, online citizens want justice for artists they enjoy. Seeing a timeline full of stolen tweets is largely unenjoyable, the banning of tweetdecks offered a more gratifying online experience. So why not help out the young underdog when you see their tweet copied or their trend misappropriated?

Epilogue

For decades the internet has been a playground for young people to express their creativity. The internet has invaded traditional media and will continue disrupting the media landscape. Keara Wilson has taken her viral dance and become a full-fledged influencer with merch and major brand sponsorships. This would have never happened if it weren’t for the internet emphasizing that she get her dance credits. Still, Wilson’s outcome is rare. New dances, funny tweets, and songs are going viral every day with regular people behind them. Getting lost in the shuffle with no credit happens more times than not. As the internet is constantly evolving and Gen Z is steering it, young creators must regain their power over the herd of sharing.