Diploma is the New Black: The Importance of the Bedford Hills College Program

Reading Time: 4 minutes“We want to intellectually engage in order to really think about the world and ourselves and change the world and ourselves.” says Judith Clark, 72, former inmate of Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for nearly 40 years.

Located in Bedford Hills, New York is the state’s largest women’s maximum-security prison called Bedford Hills Correctional Facility.

Since its start in 1997, Marymount Manhattan College (MMC) has awarded over 248 degrees to incarcerated people through the Bedford Hills College Program. These varying degrees feature Associate of Arts Degrees in Social Sciences and Bachelor of Arts degrees in Sociology or Politics and Human Rights.

The Bedford Hills College Program is a program that MMC offers to incarcerated women at the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility.

“It plays a force in building a positive community inside.” says Clark.

After the Covid-19 pandemic hit, the Bedford Hills College Program was impacted severely and eventually came to a halt. Now as the pandemic gets more under control, the program is starting back up again.

The problem is that students have yet to come back with it.

At a recent panel in the Regina Peruggi Room at Marymount Manhattan College, Clark spoke with fellow released women on her time incarcerated and the importance of the Bedford Hills College Program’s impact while inside.

The panel featured a photo series art installation titled “Looking Inside: Portraits of Women Serving Life Sentences”. Photographer Sara Bennett was in attendance as well.

“Looking Inside: Portraits of Women Serving Life Sentences” by Sara Bennett featured in Marymount Manhattan College’s campus.

As analyzed by the Rand Organization, Prison Education programs are the most effective way to reduce recidivism in a prison. Clark and the other released women all agreed.

In a 2013 study, they found that “Inmates who participate in correctional education programs had a 43 percent lower odds of recidivating than those who did not.”

Another piece published in 2001 focused on the impacts of high-security prison education programs. It featured research from an inmate research team that Clark was actually a part of.

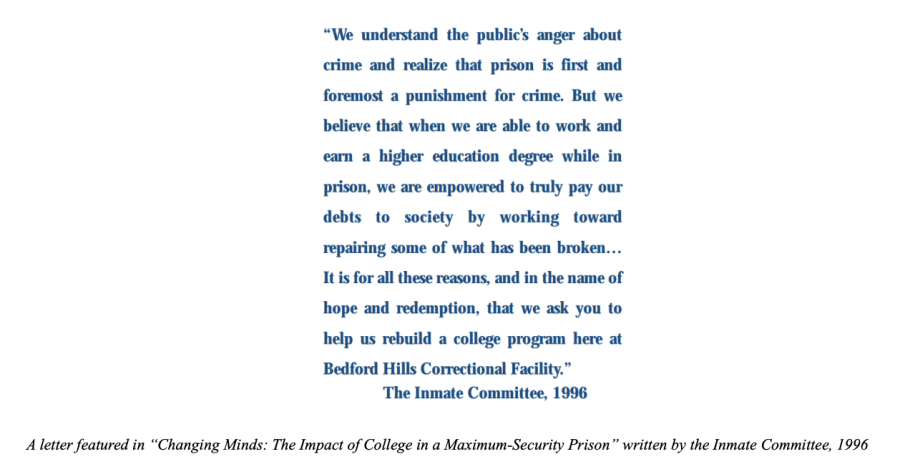

The piece is titled “Changing Minds: The Impact of College in a Maximum-Security Prison”.

In this piece, there were findings that higher education programs in high-security prison settings are actually cost beneficial as well, due to these lower reincarceration rates.

A letter featured in “Changing Minds: The Impact of College in a Maximum-Security Prison” written by the Inmate Committee, 1996

Judith Clark arrived at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility in 1983 for a 75 years to life sentence. She earned her Master of Arts degree while incarcerated.

Clark also detailed how she was someone who helped initiate the creation of the Bedford Hills College Program.

“It is amazing we’re here in a room named after Regina Peruggi because she really was instrumental in our efforts in getting the Bedford Hills College Program started.” Clark said.

After the passing of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, incarcerated individuals and prisons started to face longer sentences, and fewer programs/funding. This ended most programs available.

“It was devastating. It just took away this life force of hope and challenge and transformation that college can be.”

“The year it shut down, I was actually getting my Master’s degree and my friend was getting her GED and she was like “Judy, we have to do something cause I can’t do my 25 years and not get a college degree. I can’t do that”

“So a year later…we built a committee that was representative of people who had been in college, people who wanted to be in college, and we went to the superintendent and we said we want to build a college program that would be privately funded.”

Clark details how her committee was how she got in touch with Regina Peruggi, who then helped them get in touch with the academic community in NYC.

“There had to be a vibrant place where we gathered in classes, discussed things, could engage in a social activity of exploration. That was our comminative in terms of building that college program.”

Clark being a foundational member in the Bedford Hills College Program gives her strong insight as to how the program is an important tool to being incarcerated and to be released.

Originally, the BHCP primarily offered a degree in Sociology.

“There’s this concept called “The Sociological Imagination” and what that is is the ability to understand one’s personal troubles in a social context. And because you understand that, you can then come together in a social context to change those circumstances.”

Clark’s time while studying sociology in prison helped her and her fellow classmates face thought provoking processes that provided self evaluation.

Clark remembers her time researching for “Changing Minds” and uses those experiences to help exemplify the impact both in and out of prison that the College Program has on people.

“I remember my friend was one of the people I interviewed, and she said “I did not have the words to understand or express my remorse until I was in college. Now I understand at a deep enough level, that I can go to the depth that I need to go to to take full responsibility.” That’s what college means outside and in.”

The Bedford Hills College Program is changing lives by providing the space and the process that inmates need to be able to succeed and reacclimate back into society. These second chances are what’s important in keeping people from returning to prison.

Not only does the program offer success outside the walls of Bedford Hills, but impact the inmates while they’re serving inside as well.

“I remember this class that I took called “Philosophy of the Social Sciences” and the question the Professor asked was “do we have free will? Is there such a thing as free will?”. He said something in that class that it was his belief we cannot control our circumstances necessarily, but we do have the free will to decide our own attitude towards our circumstances.” says Clark.

She adds that this was an important, humanizing experience for her in prison.

“I never forgot that, because it sort of became the way I thought about how I needed to do my time. I couldn’t control whether or not I was there, I couldn’t control what I had done to get myself there. I could decide how I wanted to live in the face of my life sentence.”