Out of Place: A Feminist Look at the Collection

March 16, 2020

Walking into the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, one sees walls of abstract art surrounding a dining table. At this table, there are place settings for 39 historical and mythical women, and the space also honors 999 other women, whose names are written in gold on the tile floor beneath the triangular table. The ambiance of strength and power immediately resonates with everyone who gets to witness the beauty of female art.

The Brooklyn Museum is currently the home of the exhibit, Out of Place: A Feminist Look at the Collection, which includes work by forty-four artists and The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago. It is truly an emotional and empowering feeling to be in a room full of work by only female artists. Since March is Women’s History Month, it is even more relevant to visit this exhibit. 2020 is also the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage.

Out of Place uses a feminist lens to look at how museums have often ignored and devalued the work of women and people of color. This exhibit particularly challenges the institutional boundaries that orthodoxical museums have created to define art. These artists featured in the exhibit have created abstract pieces using a wide range of materials. Art is meant to be unconventional, and these women have honed in on the injustices women have faced in the art world and beyond.

In the first hall of the gallery, a colorful and intriguing painting draws patrons closer to look at the Buried Images. Joan Synder, who participated in the Feminist Movement, uses irregular dripping and smudging techniques to create a beautiful depiction of birth, loss, children, home, nature, and travel. Although the piece is shrouded in different colors and clusters of different brushstrokes, it emanates the universal meaning of life and death.

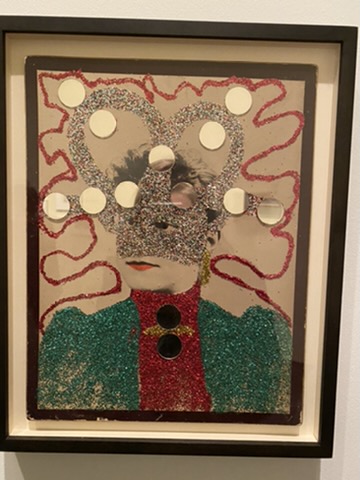

Turning the corner of the first hall, there are three untitled pieces by May Wilson. Untitled I and II stand out because they are albumen portraits covered in sparkles and have circular mirrors attached. There is a print of a person underneath, and Wilson covered the upper body and part of the face with glitter. Her other piece, Untitled 1977 is a square wooden base with two black boots attached. Wilson often uses obscure objects and different shapes and angles because of her interest in avant-garde art. She left her home and husband in Maryland to pursue her art career in New York City, earning her the title “Grandma Moses of the Underground.” Her art mainly challenges the stereotypical ideas of beauty and the societal norms surrounding women and their place in society.

In the Domestic Space section of the exhibit, the artists use everyday items from their home or workspace to cross the barrier of what is considered “women’s work” and “domestic labor” in the 1960s and 1970s. For instance, May Wilson uses a pair of women’s work boots to highlight the ideal of beauty at the time. A lot of these objects are carefully placed to show how confining and entrapping it feels to live in a sexist society.

A glass display holds a few tiny and delicate pieces, including a little boot with spikes all on the outer surface. This particular piece stands out because it is a child’s boot with prickly thorns, and the boot is filled with hair, which only creates more questions. Nancy Youdelman, who attended Fresno State University for costume design and also participated in Judy Chicago’s Feminist Art Program, created the Thorn Shoe. This piece symbolizes the pain and suffocation that results from motherhood and having children in a patriarchal society. Women are often expected to sacrifice their entire existence when having children. Youdelman’s piece challenges these expectations. There is more to motherhood than staying at home.

After the Domestic Space, there is a dark corridor painted red, leading patrons into The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago. It feels like those who enter are going down a hallway into a wonderland of sorts. Chicago created banners with the lines of her poem, “The Merger Poem,” which leads patrons to the dining table. The last banner reads “And then Everywhere was Eden Once again,” written in cursive. The Heritage Floor features a triangular table with 39 place settings for the “guests of honor” who have been misrepresented or left out of history books altogether. This room evokes an emotion of solidarity and hope for equity in the future.

Each guest has an intricately designed placemat with their name stitched in cursive. The plates are painted in a particular theme, significant for the specific person. However, all the plates are shaped like butterflies or vulvar forms. Chicago uses vulvar forms to signify women’s struggles and achievements. There are placemats for Virginia Woolf, Margaret Sanger, Mary Wollstonecraft, Sacajawea, Sojourner Truth, and 33 other powerful women. To experience The Dinner Party is unlike any other exhibit because it brings together all the women who have been suppressed in history as a result of being a female. Chicago spent five years making this work of art “to end the ongoing cycle of omission in which women were written out of the historical record.”

The final room of Out of Place holds more striking pieces made out of a wide array of materials. On the back wall, there is a warrior woman made out of “paint, metal screws, metal hardware, plastic beads, plastic bullets, zipper, synthetic fabric, aluminum foil, cord, wood, on Masonite on a board,” according to the description. Dindga McCannon made Revolutionary Sister in 1971 to give the people a female warrior. McCannon was inspired by the shape of the statue of liberty for the body of her warrior. This Revolutionary Sister is a representation of the freedom of those who have been restricted by the boundaries of society. It is freedom for African Americans and women. According to McCannon’s description, she uses red to represent bloodshed, green to represent Africa, and black for the people. She creates a symbol for what liberty should look like.

It is liberating to be surrounded by beautiful and heart-wrenching art all made by females. Recognizing the impact these female artists have made in the art world to break down conformity and stereotypes is especially important during Women’s History Month. This year it is even more important as it is the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment, which gave women the right to vote. Although 100 years have passed, women still struggle to have complete equality.

Out of Place: A Feminist Look at the Collection is a truly transformative experience, and the public will be able to visit in through September 13, 2020. In addition to the Brooklyn Museum, the New York Historical Society just opened the Women March exhibit, showing the history of women’s collective action to march for their rights and the rights of others. Women March will be open for visitors through August 30, 2020.