Racial Health Disparities In The COVID-19 Era

Reading Time: 6 minutesThe Netflix TV show, Evil, follows, questioning psychologist Kristen Bouchard (Katja Herbers) and seminarian David Acosta (Mike Colter) following cases that test what they believe are along the lines of science and paranormal. This fictional show goes into different aspects of faith from different cultures and the occult, but it shows instances of racial disparities in a time where it happened more than often.

One episode in particular shows one of the main characters, David Acosta, a black man that goes through his own deal of trials and tribulations, but one of them lands him in the hospital. A hospital that focuses its time and energy on taking care and resituating its white patients more so than its black patients. Once awakened from his procedure of being stabbed, he hears of this “evil nurse” who intentionally kills black patients. They call her the “angel of death.” In his foggy state of mind, he sees gruesome images of black patients being taken away in the middle of the night to be sacrificed and experimented on.

But what happens when this fictional situation isn’t so far off from the real world. The medical racism in Evil reveals the horrors of what black people in America go through on a daily basis when trying to receive treatment from medical professionals. Myths that create bias in the medical industry stemming from a history of prejudiced beliefs that Black Americans’ lives were less important than white lives. This prevented thousands of people from being saved and treated.

The real-life horror for Black Americans of being neglected and uncared for in the healthcare system is resulting in death and serious injuries to the community. Black Americans have been abused by the healthcare system for years, the result: a widespread lack of trust in mainstream medicine.

According to a recent survey by Pew Research Center, only 42% of Black Americans say they would get the vaccines if they were available today compared to over 60 percent of White and Hispanic adults who say they would immediately take the vaccine.

The reasoning behind this daunting statistic has nothing to do with paranoia, and everything to do with decades of racial disparities within the American healthcare system. Racial and ethnic minority groups are unequally affected by the economic, social, and secondary health consequences of COVID-19 because of their lack of access to and distribution of resources. This puts many racial and ethnic minority groups at increased risk of getting sick, having more severe illnesses, and dying from COVID-19.

It is proven time and time again that common diseases that often affect Black Americans more than any other race, are not always taken seriously or are not successfully treated. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and The Undefeated, A majority of African Americans have low levels of trust in the health care system, expressing much less confidence in doctors and hospitals than white people.

One of the diseases among the black American community is Sickle Cell Disease (SCD), more commonly, Sickle Cell Anemia. With this disease, the hemoglobin is abnormal, causing the red blood cells to form a “C” or sickle shape. Sickle cells can get stuck and block blood flow, causing pain and infections, also known as a “sickle cell crisis.” The Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that Sickle Cell Anemia occurs in about 1 out of every 365 black American births and about 1 in 13 black American babies is born with the sickle cell trait.

“My father has sickle cell, which means I grew up frequently visiting my father in the hospital, and when I became old enough, I started driving him there when he was too weak to drive himself.” Amarachi Ogan, whose father suffers from Sickle Cell Disease, expresses her concern for her father’s medical care. “Because his doctor is so unfamiliar with sickle cell despite my father going to him for upward of a decade, I am always nervous that my father won’t come home from the hospital.”

A recent study found that, in general, academic family physicians see few Sickle Cell patients and are concerned with their ability to treat SCD and SCD-related health complications. In fact, only 1 in 5 surveyed physicians reported being comfortable treating patients with SCD.

“A few months ago, my father was in the hospital for almost a month because of a crisis that wasn’t properly handled,” Ogan explained. The crisis affected his entire body, his joints were inflamed, and it caused him pain to make any movements. Ogan revealed that her father’s hands were so swollen, they had to call firefighters to cut his wedding ring off his finger because his hands were almost double their size and his finger was suffering from the pressure of the ring and was at risk of tearing open.

The facts remain the same about improper treatment of many other diseases that mostly affect Black Americans. With preterm delivery, premature black babies in the U.S die at just over two times the rate of white babies in the first year of their life. According to The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for every 1,000 live births, 4.8 white infants die in the first year of life. For black babies, that number is 11.7. The majority of those black infants that die are born prematurely because Black mothers have a higher risk of going into early labor.

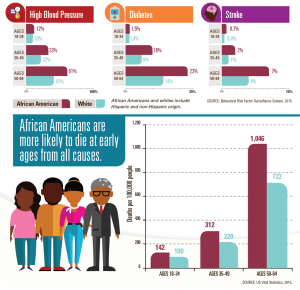

According to The National Stroke Association, black Americans are more impacted by stroke than any other racial group within the American population. Black Americans are twice as likely to die from stroke as white Americans and their rate of first strokes is almost double that of white Americans.

According to The US Department of Health and Human Services Office Of Minority Health, Black Americans are almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with diabetes as non-Hispanic whites. In addition, Black Americans are more likely to suffer complications from diabetes.

One study of 400 hospitals in the United States by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) showed that black patients with heart disease received older, cheaper, and more conservative treatments than their white counterparts. Black patients were less likely to receive coronary bypass operations and angiography. After surgery, they are discharged earlier and at almost inappropriate stages from the hospital than white patients.

“I truly believe that if my father had a disease that was a common disease for white people, not only would all doctors be well versed in it, but there would be centers dedicated to the study of it,” Ogan explained. “Because Sickle Cell Anemia disproportionately affects Black people, there is a lack of awareness in the health care system because they do not consider it a worthy enough cause.”

The American Bar Association found that “racial and ethnic minorities receive lower-quality health care than white people—even when insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions are comparable.” So, what does all of this mean in the COVID-19 era?

Well, racial and ethnic minority groups have disproportionately higher hospitalization rates from COVID among every age group, including children aged younger than 18 years. This means that there is a chance of a significant increase in medical racism, health disparities, and micro-aggression, but this time the patients will have to face it with no family members or friends around to fight for them.

Ogan dealt with a similar problem upon her father being admitted to the hospital alone. With him being immunocompromised because of his sickle cell anemia and surrounded by COVID patients, Ogan was filled with anxiety.

“Before the pandemic, my mother always visited my dad throughout his hospital stays to make sure he was taken care of and taken seriously, as the nurses often didn’t believe him when he complained about pain. Now that my mother isn’t allowed to check on him and his treatment, I constantly worry about him when he is at the hospital.”

These fears are rightfully valid considering Black Americans are 37% more likely to die than white Americans from COVID-19. Those higher case fatality rates for diagnosed people of color are on top of the increased infection rates for those unable to isolate at home because they are essential workers and don’t have the same access to treatment as everyone else.

The Black community has been hit hard by COVID-19 and a lasting pandemic. Many of the factors that drive racial bias — housing, food insecurity, access to transportation, and health care have all been affected as well. But this isn’t anything new.

Ogan concluded, “I don’t think that COVID has created racial disparities or microaggressions. They have always been present, and those that haven’t experienced them or noticed them are probably part of the problem.”

Links to educate yourself on racial health disparities and microaggressions:

- AAMC https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/racism-and-health

- CDC https://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/strategies2016/index.html

- Health Affairs https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200716.620294/full/

- Michigan Health https://healthblog.uofmhealth.org/lifestyle/health-inequality-actually-a-black-and-white-issue-research-says

- KFF https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/disparities-in-health-and-health-care-five-key-questions-and-answers/

- Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/04/10/4-reasons-coronavirus-is-hitting-black-communities-so-hard/

- American Bar https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/the-state-of-healthcare-in-the-united-states/racial-disparities-in-health-care/

Rayiah Ross is a senior majoring in digital journalism and minoring in creative writing. She has a focus on cultural criticism and social commentary.

Najla Alexander is the Features Editor and Crime Reporter for The Monitor. She is Majoring in Digital Journalism and Minoring in Forensic Psychology. Her...